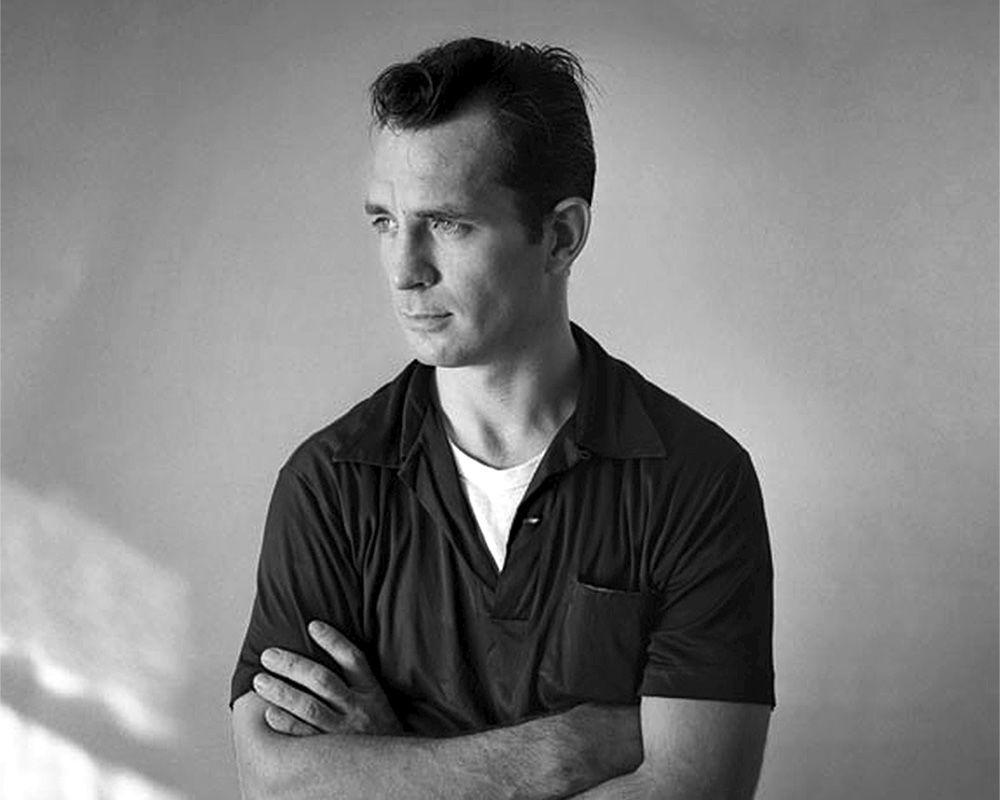

JACK KEROUAC, CA. 1956. PHOTOGRAPH BY TOM PALUMBO

The Kerouacs have no telephone. Ted Berrigan had contacted Kerouac some months earlier and had persuaded him to do the interview. When he felt the time had come for their meeting to take place, he simply showed up at the Kerouacs’s house. Two friends, poets Aram Saroyan and Duncan McNaughton, accompanied him. Kerouac answered his ring; Berrigan quickly told him his name and the visit’s purpose. Kerouac welcomed the poets, but before he could show them in, his wife, a very determined woman, seized him from behind and told the group to leave at once.

“Jack and I began talking simultaneously, saying ‘Paris Review!’ ‘Interview!’ etc.,” Berrigan recalls, “while Duncan and Aram began to slink back toward the car. All seemed lost, but I kept talking in what I hoped was a civilized, reasonable, calming, and friendly tone of voice, and soon Mrs. Kerouac agreed to let us in for twenty minutes, on the condition that there be no drinking.

“Once inside, as it became evident that we actually were in pursuit of a serious purpose, Mrs. Kerouac became more friendly, and we were able to commence the interview. It seems that people still show up constantly at the Kerouacs’s looking for the author of On the Road, and stay for days, drinking all the liquor and diverting Jack from his serious occupations.

“As the evening progressed the atmosphere changed considerably, and Mrs. Kerouac, Stella, proved a gracious and charming hostess. The most amazing thing about Jack Kerouac is his magic voice, which sounds exactly like his works. It is capable of the most astounding and disconcerting changes in no time flat. It dictates everything, including this interview.

“After the interview, Kerouac, who had been sitting throughout the interview in a President Kennedy-type rocker, moved over to a big poppa chair and said, ‘So you boys are poets, hey? Well, let’s hear some of your poetry.’ We stayed for about an hour longer and Aram and I read some of our things. Finally, he gave each of us a signed broadside of a recent poem of his, and we left.”

INTERVIEWER

Could we put the footstool over here to put this on?

STELLA

Yes.

JACK KEROUAC

God, you’re so inadequate there, Berrigan.

INTERVIEWER

Well, I’m no tape-recorder man, Jack. I’m just a big talker, like you. OK, we’re off.

KEROUAC

Okay? [Whistles.] Okay?

INTERVIEWER

Actually I’d like to start … The first book I ever read by you, oddly enough, since most people first read On the Road … the first one I read was The Town and the City …

KEROUAC

Gee!

INTERVIEWER

I checked it out of the library …

KEROUAC

Gee! Did you read Doctor Sax? Tristessa?

INTERVIEWER

You better believe it. I even read Rimbaud. I have a copy of Visions of Cody that Ron Padgett bought in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

KEROUAC

Screw Ron Padgett! You know why? He started a little magazine called White Dove Review in Kansas City, was it? Tulsa? Oklahoma … yes. He wrote, “Start our magazine off by sending us a great big poem.” So I sent him “The Thrashing Doves.” And then I sent him another one and he rejected the second one because his magazine was already started. That’s to show you how punks try to make their way by scratching down on a man’s back. Aw, he’s no poet. You know who’s a great poet? I know who the great poets are.

INTERVIEWER

Who?

KEROUAC

Let’s see, is it … William Bissett of Vancouver. An Indian boy. Bill Bissett, or Bissonnette.

INTERVIEWER

Let’s talk about Jack Kerouac.

KEROUAC

He’s not better than Bill Bissett, but he’s very original.

INTERVIEWER

Why don’t we begin with editors. How do you …

KEROUAC

OK. All my editors since Malcolm Cowley have had instructions to leave my prose exactly as I wrote it. In the days of Malcolm Cowley, with On the Road and The Dharma Bums, I had no power to stand by my style for better or for worse. When Malcolm Cowley made endless revisions and inserted thousands of needless commas like, say, “Cheyenne, Wyoming” (why not just say “Cheyenne Wyoming” and let it go at that, for instance), why, I spent five hundred dollars making the complete restitution of the Bums manuscript and got a bill from Viking Press called “Revisions.” Ha ho ho. And so you asked about how do I work with an editor … well nowadays I am just grateful to him for his assistance in proofreading the manuscript and in discovering logical errors, such as dates, names of places. For instance, in my last book I wrote Firth of Forth then looked it up, on the suggestion of my editor, and found that I’d really sailed off the Firth of Clyde. Things like that. Or I spelled Aleister Crowley “Alisteir,” or he discovered little mistakes about the yardage in football games … and so forth. By not revising what you’ve already written you simply give the reader the actual workings of your mind during the writing itself: you confess your thoughts about events in your own unchangeable way … Well, look, did you ever hear a guy telling a long wild tale to a bunch of men in a bar and all are listening and smiling, did you ever hear that guy stop to revise himself, go back to a previous sentence to improve it, to defray its rhythmic thought impact. … If he pauses to blow his nose, isn’t he planning his next sentence? And when he lets that next sentence loose, isn’t it once and for all the way he wanted to say it? Doesn’t he depart from the thought of that sentence and, as Shakespeare says, “forever holds his tongue” on the subject, since he’s passed over it like a part of a river that flows over a rock once and for all and never returns and can never flow any other way in time? Incidentally, as for my bug against periods, that was for the prose in October in the Railroad Earth, very experimental, intended to clack along all the way like a steam engine pulling a one-hundred-car freight with a talky caboose at the end, that was my way at the time and it still can be done if the thinking during the swift writing is confessional and pure and all excited with the life of it. And be sure of this, I spent my entire youth writing slowly with revisions and endless rehashing speculation and deleting and got so I was writing one sentence a day and the sentence had no FEELING. Goddamn it, FEELING is what I like in art, not CRAFTINESS and the hiding of feelings.

INTERVIEWER

What encouraged you to use the “spontaneous” style of On the Road?

KEROUAC

I got the idea for the spontaneous style of On the Road from seeing how good old Neal Cassady wrote his letters to me, all first person, fast, mad, confessional, completely serious, all detailed, with real names in his case, however (being letters). I remembered also Goethe’s admonition, well Goethe’s prophecy that the future literature of the West would be confessional in nature; also Dostoyevsky prophesied as much and might have started in on that if he’d lived long enough to do his projected masterwork, The Life of a Great Sinner. Cassady also began his early youthful writing with attempts at slow, painstaking, and all-that-crap craft business, but got sick of it like I did, seeing it wasn’t getting out his guts and heart the way it felt coming out. But I got the flash from his style. It’s a cruel lie for those West Coast punks to say that I got the idea of On the Road from him. All his letters to me were about his younger days before I met him, a child with his father, et cetera, and about his later teenage experiences. The letter he sent me is erroneously reported to be a thirteen-thousand-word letter … no, the thirteen-thousand-word piece was his novel The First Third, which he kept in his possession. The letter, the main letter I mean, was forty thousand words long, mind you, a whole short novel. It was the greatest piece of writing I ever saw, better’n anybody in America, or at least enough to make Melville, Twain, Dreiser, Wolfe, I dunno who, spin in their graves. Allen Ginsberg asked me to lend him this vast letter so he could read it. He read it, then loaned it to a guy called Gerd Stern who lived on a houseboat in Sausalito, California, in 1955, and this fellow lost the letter: overboard I presume. Neal and I called it, for convenience, the Joan Anderson Letter … all about a Christmas weekend in the pool halls, hotel rooms and jails of Denver, with hilarious events throughout and tragic too, even a drawing of a window, with measurements to make the reader understand, all that. Now listen: this letter would have been printed under Neal’s copyright, if we could find it, but as you know, it was my property as a letter to me, so Allen shouldn’t have been so careless with it, nor the guy on the houseboat. If we can unearth this entire forty-thousand-word letter Neal shall be justified. We also did so much fast talking between the two of us, on tape recorders, way back in 1952, and listened to them so much, we both got the secret of LINGO in telling a tale and figured that was the only way to express the speed and tension and ecstatic tomfoolery of the age … Is that enough?

INTERVIEWER

How do you think this style has changed since On the Road?

KEROUAC

What style? Oh, the style of On the Road. Well as I say, Cowley riddled the original style of the manuscript there, without my power to complain, and since then my books are all published as written, as I say, and the style has varied from the highly experimental speed-writing of Railroad Earth to the ingrown toenail packed mystical style of Tristessa, the Notes from Underground (by Dostoyevsky) confessional madness of The Subterraneans, the perfection of the three as one in Big Sur, I’d say, which tells a plain tale in a smooth buttery literate run, to Satori in Paris, which is really the first book I wrote with drink at my side (cognac and malt liquor) … and not to overlook Book of Dreams, the style of a person half-awake from sleep and ripping it out in pencil by the bed … yes, pencil … what a job! Bleary eyes, insaned mind bemused and mystified by sleep, details that pop out even as you write them you don’t know what they mean, till you wake up, have coffee, look at it, and see the logic of dreams in dream language itself, see? … And finally I decided in my tired middle age to slow down and did Vanity of Duluoz in a more moderate style so that, having been so esoteric all these years, some earlier readers would come back and see what ten years had done to my life and thinking … which is after all the only thing I’ve got to offer, the true story of what I saw and how I saw it.

INTERVIEWER

You dictated sections of Visions of Cody. Have you used this method since?

KEROUAC

I didn’t dictate sections of Visions of Cody. I typed up a segment of taped conversation with Neal Cassady, or Cody, talking about his early adventures in LA. It’s four chapters. I haven’t used this method since; it really doesn’t come out right, well, with Neal and with myself, when all written down and with all the Ahs and the Ohs and the ahums and the fearful fact that the damn thing is turning and you’re forced not to waste electricity or tape … Then again, I don’t know, I might have to resort to that eventually; I’m getting tired and going blind. This question stumps me. At any rate, everybody’s doing it, I hear, but I’m still scribbling. McLuhan says we’re getting more oral so I guess we’ll all learn to talk into the machine better and better.

INTERVIEWER

What is that state of “Yeatsian semi-trance” which provides the ideal atmosphere for spontaneous writing?

KEROUAC

Well, there it is, how can you be in a trance with your mouth yapping away … writing at least is a silent meditation even though you’re going a hundred miles an hour. Remember that scene in La Dolce Vita where the old priest is mad because a mob of maniacs has shown up to see the tree where the kids saw the Virgin Mary? He says, “Visions are not available in all this frenetic foolishness and yelling and pushing; visions are only obtainable in silence and meditation.” Thar. Yup.

INTERVIEWER

You have said that haiku is not written spontaneously but is reworked and revised. Is this true of all your poetry? Why must the method for writing poetry differ from that of prose?

KEROUAC

No, first; haiku is best reworked and revised. I know, I tried. It has to be completely economical, no foliage and flowers and language rhythm, it has to be a simple little picture in three little lines. At least that’s the way the old masters did it, spending months on three little lines and coming up, say, with:

In the abandoned boat,

The hail

Bounces about.

That’s Shiki. But as for my regular English verse, I knocked it off fast like the prose, using, get this, the size of the notebook page for the form and length of the poem, just as a musician has to get out, a jazz musician, his statement within a certain number of bars, within one chorus, which spills over into the next, but he has to stop where the chorus page stops. And finally, too, in poetry you can be completely free to say anything you want, you don’t have to tell a story, you can use secret puns, that’s why I always say, when writing prose, “No time for poetry now, get your plain tale.”

[Drinks are served.]

INTERVIEWER

How do you write haiku?

KEROUAC

Haiku? You want to hear haiku? You see you got to compress into three short lines a great big story. First you start with a haiku situation—so you see a leaf, as I told her the other night, falling on the back of a sparrow during a great big October wind storm. A big leaf falls on the back of a little sparrow. How you going to compress that into three lines? Now in Japanese you got to compress it into seventeen syllables. We don’t have to do that in American—or English—because we don’t have the same syllabic bullshit that your Japanese language has. So you say: “Little sparrow”—you don’t have to say little—everybody knows a sparrow is little because they fall so you say:

Sparrow

with big leaf on its back—

windstorm

No good, don’t work, I reject it.

A little sparrow

when an autumn leaf suddenly sticks to its back

from the wind.

Hah, that does it. No, it’s a little bit too long. See? It’s already a little bit too long, Berrigan, you know what I mean?

INTERVIEWER

Seems like there’s an extra word or something, like when. How about leaving out when? Say:

A sparrow

an autumn leaf suddenly sticks to its back—

from the wind!

KEROUAC

Hey, that’s all right. I think when was the extra word. You got the right idea there, O’Hara! “A sparrow, an autumn leaf suddenly”—we don’t have to say suddenly do we?

A sparrow

an autumn leaf sticks to its back—

from the wind!

[Kerouac writes final version into a spiral notebook.]

INTERVIEWER

Suddenly is absolutely the kind of word we don’t need there. When you publish that will you give me a footnote saying you asked me a couple of questions?

KEROUAC

[writes] Berrigan noticed. Right?

INTERVIEWER

Do you write poetry very much? Do you write other poetry besides haiku?

KEROUAC

It’s hard to write haiku. I write long silly Indian poems. You want to hear my long silly Indian poem?

INTERVIEWER

What kind of Indian?

KEROUAC

Iroquois. As you know from looking at me. [Reads from notebook.]

On the lawn on the way to the store

forty-four years old for the neighbors to hear

hey, looka, Ma I hurt myself. Especially

with that squirt.

What’s that mean?

INTERVIEWER

Say it again.

KEROUAC

Hey, looka, Ma, I hurt myself, while on the way to the store I hurt myself I fell on the lawn I yell to my mother hey looka, Ma, I hurt myself. I add, especially with that squirt.

INTERVIEWER

You fell over a sprinkler?

KEROUAC

No, my father’s squirt into my Ma.

INTERVIEWER

From that distance?

KEROUAC

Oh, I quit. No, I know you wouldn’t get that one. I had to explain it. [Opens notebook again and reads.]

Goy means joy.

INTERVIEWER

Send that one to Ginsberg.

KEROUAC

[Reads.]

Happy people so called are hypocrites—it means

the happiness wavelength can’t work without

necessary deceit, without certain scheming and lies and

hiding. Hypocrisy and deceit, no Indians. No smiling.

INTERVIEWER

No Indians?

KEROUAC

The reason you really have a hidden hostility towards me, Berrigan, is because of the French and Indian War.

INTERVIEWER

That could be.

INTERVIEWER

I saw a football picture of you in the cellar of Horace Mann. You were pretty fat in those days.

STELLA

Tuffy! Here Tuffy! Come on, kitty …

KEROUAC

Stella, let’s have another bottle or two. Yeah, I’m going to murder everybody if they let me go. I did. Hot fudge sundaes! Boom! I used to have two or three hot fudge sundaes before every game. Lou Little …

INTERVIEWER

He was your coach at Columbia?

KEROUAC

Lou Little was my coach at Columbia. My father went up to him and said, “You sneaky long-nosed finagler …” He says, “Why don’t you let my son, Ti Jean, Jack, start in the Army game so he can get back at his great enemy from Lowell?” And Lou Little says, “Because he’s not ready.” “Who says he’s not ready?” “I say he’s not ready.” My father says, “Why you long nose banana nose big crook, get out of my sight!” And he comes stomping out of the office smoking a big cigar. “Come out of here Jack, let’s get out of here.” So we left Columbia together. And also when I was in the United States Navy during the war—1942—right in front of the admirals, he walked in and says, “Jack, you are right! The Germans should not be our enemies. They should be our allies, as it will be proven in time.” And the admirals were all there with their mouths open, and my father would take no shit from nobody—my father didn’t have nothing but a big belly about this big [gestures with arms out in front of him] and he would go POOM! [Kerouac gets up and demonstrates, by puffing his belly out in front of him with explosive force and saying “POOM!”] One time he was walking down the street with my mother, arm in arm, down the Lower East Side. In the old days, you know, the 1940s. And here comes a whole bunch of rabbis walking arm in arm … tee-dah tee-dah tee-dah … and they wouldn’t part for this Christian man and his wife. So my father went POOM! And he knocked a rabbi right in the gutter. Then he took my mother and walked on through.

Now, if you don’t like that, Berrigan, that’s the history of my family. They don’t take no shit from nobody. In due time I ain’t going to take no shit from nobody. You can record that.

Is this my wine?

INTERVIEWER

Was The Town and the City written under spontaneous composition principles?

KEROUAC

Some of it, sire. I also wrote another version that’s hidden under the floorboards, with Burroughs.

INTERVIEWER

Yes, I’ve heard rumors of that book. Everybody wants to get at that book.

KEROUAC

It’s called And the Hippos Were Boiled in Their Tanks. The hippos. Because Burroughs and I were sitting in a bar one night and we heard a newscaster saying “ … and so the Egyptians attacked blah blah … and meanwhile there was a great fire in the zoo in London and the fire raced across the fields and the hippos were boiled in their tanks! Goodnight everyone!” That’s Bill, he noticed that. Because he notices them kind of things.

INTERVIEWER

You really did type up his Naked Lunch manuscript for him in Tangier?

KEROUAC

No … the first part. The first two chapters. I went to bed, and I had nightmares … of great long bolognas coming out of my mouth. I had nightmares typing up that manuscript … I said, “Bill!” He said, “Keep typing it.” He said, “I bought you a goddamn kerosene stove here in North Africa, you know.” Among the Arabs … it’s hard to get a kerosene stove. I’d light up the kerosene stove, and take some bedding and a little pot, or kef as we called it there … or maybe sometimes hashish … there, by the way, it’s legal … and I’d go toke toke toke toke and when I went to bed at night, these things kept coming out of my mouth. So finally these other guys showed up like Alan Ansen and Allen Ginsberg, and they spoiled the whole manuscript because they didn’t type it up the way he wrote it.

INTERVIEWER

Grove Press has been issuing his Olympia Press books with lots of changes and things added.

KEROUAC

Well, in my opinion Burroughs hasn’t given us anything that would interest our breaking hearts since he wrote like he did in Naked Lunch. Now all he does is that “breakup” stuff; it’s called … where you write a page of prose, you write another page of prose … then you fold it over and you cut it up and you put it together … and shit like that …

INTERVIEWER

What about Junky, though?

KEROUAC

It’s a classic. It’s better than Hemingway—it’s just like Hemingway but even a little better too. It says: “Danny comes into my pad one night and says, ‘Hey, Bill, can I borrow your sap.’” Your sap—do you know what a sap is?

INTERVIEWER

A blackjack?

KEROUAC

It’s a blackjack. Bill says, “I pulled out my underneath drawer, and underneath some nice shirts I pulled out my blackjack. I gave it to Danny and said, ‘Now don’t lose it, Danny’—Danny says, ‘Don’t worry I won’t lose it.’ He goes off and loses it.”

Sap … blackjack … that’s me. Sap … blackjack.

INTERVIEWER

That’s a haiku: Sap, blackjack, that’s me. You better write that down.

KEROUAC

No.

INTERVIEWER

Maybe I’ll write that down. Do you mind if I use that one?

KEROUAC

Up your ass with Mobil gas!

INTERVIEWER

You don’t believe in collaborations? Have you ever done any collaborations, other than with publishers?

KEROUAC

I did a couple of collaborations in bed with Bill Cannastra in lofts. With blondes.

INTERVIEWER

Was he the guy that tried to climb off the subway train at Astor Place, in Holmes’s Go?

KEROUAC

Yes. Yeah, well he says, “Let’s take all our clothes off and run around the block” … It was raining you know. Sixteenth Street off Seventh Avenue. I said, “Well, I’ll keep my shorts on”—he says, “No, no shorts.” I said, “I’m going to keep my shorts on.” He said, “All right, but I’m not going to wear mine.” And we trot-trot-trot-trot down the block. Sixteenth to Seventeenth … and we come back and run up the stairs—nobody saw us.

INTERVIEWER

What time of day?

KEROUAC

But he was absolutely naked … about three or four A.M. It rained. And everybody was there. He was dancing on broken glass and playing Bach. Bill was the guy who used to teeter off his roof—six flights up, you know? He’d go, “You want me to fall?” We’d say, “No, Bill, no.” He was an Italian. Italians are wild, you know.

INTERVIEWER

Did he write? What did he do?

KEROUAC

He says, “Jack, come with me and look down through this peephole.” We looked down through the peephole, we saw a lot of things … into his toilet.

I said, “I’m not interested in that, Bill.” He said, “You’re not interested in anything.” Auden would come the next day, the next afternoon, for cocktails. Maybe with Chester Kallman. Tennessee Williams.

INTERVIEWER

Was Neal Cassady around in those days? Did you already know Neal Cassady when you were involved with Bill Cannastra?

KEROUAC

Oh yes, yes, ahem … he had a great big pack of pot. He always was a pot happy man.

INTERVIEWER

Why do you think Neal doesn’t write?

KEROUAC

He has written … beautifully! He has written better than I have. Neal’s a very funny guy. He’s a real Californian. We had more fun than five thousand Socony Gasoline Station attendants can have. In my opinion he’s the most intelligent man I’ve ever met in my life. Neal Cassady. He’s a Jesuit by the way. He used to sing in the choir. He was a choirboy in the Catholic churches of Denver. And he taught me everything that I now do believe about anything that there may be to be believed about divinity.

INTERVIEWER

About Edgar Cayce?

KEROUAC

No, before he found out about Edgar Cayce he told me all these things in the section of the life he led when he was on the road with me—he said, “We know God, don’t we Jack?” I said, “Yessir boy.” He said, “Don’t we know that nothing’s going to happen wrong?” “Yessir.” “And we’re going to go on and on … and hmmmmm ja-bmmmmmmm …” He was perfect. And he’s always perfect. Every time he comes to see me I can’t get a word in edgewise.

INTERVIEWER

You wrote about Neal playing football in Visions of Cody.

KEROUAC

Yes, he was a very good football player. He picked up two beatniks that time in blue jeans in North Beach, Frisco. He said, “I got to go, bang bang, do I got to go?” He’s working on the railroad … had his watch out … “Two-fifteen, boy I got to be there by two-twenty. I tell you boys drive me over down there so I be on time with my train … So I can get my train on down to”—what’s the name of that place—San Jose? They say, “Sure kid” and Neal says, “Here’s the pot.” So—“We maybe look like great beatniks with great beards … but we are cops. And we are arresting you.”

So, a guy went to the jailhouse and interviewed him from the New York Post and he said, “Tell that Kerouac if he still believes in me to send me a typewriter.” So I sent Allen Ginsberg one hundred dollars to get a typewriter for Neal. And Neal got the typewriter. And he wrote notes on it, but they wouldn’t let him take the notes out. I don’t know where the typewriter is. Genet wrote all of Our Lady of the Flowers in the shithouse … the jailhouse. There’s a great writer, Jean Genet. He kept writing and kept writing until he got to a point where he was going to come by writing about it … until he came into his bed—in the can. The French can. The French jail. Prison. And that was the end of the chapter. Every chapter is Genet coming off. Which I must admit Sartre noticed.

INTERVIEWER

You think that’s a different kind of spontaneous writing?

KEROUAC

Well, I could go to jail and I could write every night a chapter about Magee, Magoo, and Molly. It’s beautiful. Genet is really the most honest writer we’ve had since Kerouac and Burroughs. But he came before us. He’s older. Well, he’s the same age as Burroughs. But I don’t think I’ve been dishonest. Man, I’ve had a good time! God, man, I rode around this country free as a bee. But Genet is a very tragic and beautiful writer. And I give them the crown. And the laurel wreath. I don’t give the laurel wreath to Richard Wilbur! Or Robert Lowell. Give it to Jean Genet and William Seward Burroughs. And to Allen Ginsberg and to Gregory Corso, especially.

INTERVIEWER

Jack, how about Peter Orlovsky’s writings. Do you like Peter’s things?

KEROUAC

Peter Orlovsky is an idiot!! He’s a Russian idiot. Not even Russian, he’s Polish.

INTERVIEWER

He’s written some fine poems.

KEROUAC

Oh yeah. My … what poems?

INTERVIEWER

He has a beautiful poem called “Second Poem.”

KEROUAC

“My brother pisses in the bed … and I go in the subway and I see two people kissing …”

INTERVIEWER

No, the poem that says “it’s more creative to paint the floor than to sweep it.”

KEROUAC

That’s a lot of shit! That is the kind of poetry that was written by another Polish idiot who was a Polish nut called Apollinaire. Apollinaire is not his real name, you know.

There are some fellows in San Francisco that told me that Peter was an idiot. But I like idiots, and I enjoy his poetry. Think about that, Berrigan. But for my taste, it’s Gregory.

Give me one of those.

INTERVIEWER

One of these pills?

KEROUAC

Yeah. What are they? Forked clarinets?

INTERVIEWER

They’re called Obetrol. Neal is the one that told me about them.

KEROUAC

Overtones?

INTERVIEWER

Overtones? No, overcoats.

INTERVIEWER

What was that you said … at the back of the Grove anthology … that you let the line go a little longer to fill it up with secret images that come at the end of the sentence.

KEROUAC

He’s a real Armenian! Sediment. Delta. Mud. It’s where you start a poem …

As I was walking down the street one day

I saw a lake where people were cutting off my rear,

17,000 priests singing like George Burns

and then you go on …

And I’m making jokes about me

and breaking my bones in the earth

and here I am the great John Armenian

coming back to earth

now you remember where you were in the beginning and you say …

Ahaha! Tatatatadooda … Screw Turkey!

See? You remembered the line at the end … you lose your mind in the middle.

INTERVIEWER

Right.

KEROUAC

That applies to prose as well as poetry.

INTERVIEWER

But in prose you are telling a story …

KEROUAC

In prose you make the paragraph. Every paragraph is a poem.

INTERVIEWER

Is that how you write a paragraph?

KEROUAC

When I was running downtown there, and I was going to do this, and I was laying there, with that girl there, and a guy took out his scissors and I took him inside there, he showed me some dirty pictures. And I went out and fell downstairs with the potato bags.

INTERVIEWER

Did you ever like Gertrude Stein’s work?

KEROUAC

Never interested me too much. I liked “Melanctha” a little bit.

I should really go to school and teach these kids. I could make two thousand bucks a week. You can’t learn these things. You know why? Because you have to be born with tragic fathers.

INTERVIEWER

You can only do that if you are born in New England.

KEROUAC

Incidentally, my father said your father wasn’t tragic.

INTERVIEWER

I don’t think my father is tragic.

KEROUAC

My father said that INTERVIEWER … William INTERVIEWER ain’t tragic at all … he’s fulla shit. And I had a big argument with him. The Daring Young Man on the Flying Trapeze is pretty tragic, I would say.

INTERVIEWER

He was just a young man then, you know.

KEROUAC

Yeah, but he was hungry, and he was on Times Square. Flying. A young man on the flying trapeze. That was a beautiful story. It killed me when I was a kid.

INTERVIEWER

Do you remember a story by William INTERVIEWER about the Indian who came to town and bought a car and got the little kid to drive it for him?

STELLA

A Cadillac.

KEROUAC

What town was that?

INTERVIEWER

Fresno. That was Fresno.

KEROUAC

Well, you remember the night I was taking a big nap and you came up outside my window on a white horse …

INTERVIEWER

“The Summer of the Beautiful White Horse.”

KEROUAC

And I looked out the window and said, “What is this?” You said, “My name is Aram. And I’m on a white horse.”

INTERVIEWER

Mourad.

KEROUAC

“My name is Mourad,” excuse me. No, my name is … I was Aram, you were Mourad. You said, “Wake up!” I didn’t want to wake up. I wanted to sleep. My Name Is Aram is the name of the book. You stole a white horse from a farmer and you woke up me, Aram, to go riding with you.

INTERVIEWER

Mourad was the crazy one who stole the horse.

KEROUAC

Hey, what’s that you gave me there?

INTERVIEWER

Obetrol.

KEROUAC

Oh, obies.

INTERVIEWER

What about jazz and bop as influences rather than … INTERVIEWER, Hemingway, and Wolfe?

KEROUAC

Yes, jazz and bop, in the sense of a, say, a tenor man drawing a breath and blowing a phrase on his saxophone, till he runs out of breath, and when he does, his sentence, his statement’s been made … That’s how I therefore separate my sentences, as breath separations of the mind … I formulated the theory of breath as measure, in prose and verse, never mind what Olson, Charles Olson says, I formulated that theory in 1953 at the request of Burroughs and Ginsberg. Then there’s the raciness and freedom and humor of jazz instead of all that dreary analysis and things like “James entered the room, and lit a cigarette. He thought Jane might have thought this too vague a gesture …” You know the stuff. As for INTERVIEWER, yes I loved him as a teenager, he really got me out of the nineteenth-century rut I was trying to study, not only with his funny tone but also with his neat Armenian poetic—I don’t know what … he just got me … Hemingway was fascinating, the pearls of words on a white page giving you an exact picture … but Wolfe was a torrent of American heaven and hell that opened my eyes to America as a subject in itself.

INTERVIEWER

How about the movies?

KEROUAC

Yes, we’ve all been influenced by movies. Malcolm Cowley incidentally mentioned this many times. He’s very perceptive sometimes: he mentioned that Doctor Sax continually mentions urine, and quite naturally it does because I had no other place to write it but on a closed toilet seat in a little tile toilet in Mexico City so as to get away from the guests inside the apartment. There, incidentally, is a style truly hallucinated, as I wrote it all on pot. No pun intended. Ho ho.

INTERVIEWER

How has Zen influenced your work?

KEROUAC

What’s really influenced my work is the Mahayana Buddhism, the original Buddhism of Gautama ´Sàkyamuni, the Buddha himself, of the India of old … Zen is what’s left of his Buddhism, or Bodhi, after its passing into China and then into Japan. The part of Zen that’s influenced my writing is the Zen contained in the haiku, like I said, the three-line, seventeen-syllable poems written hundreds of years ago by guys like Bashō, Issa, Shiki, and there’ve been recent masters. A sentence that’s short and sweet with a sudden jump of thought in it is a kind of haiku, and there’s a lot of freedom and fun in surprising yourself with that, let the mind willy-nilly jump from the branch to the bird. But my serious Buddhism, that of ancient India, has influenced that part in my writing that you might call religious, or fervent, or pious, almost as much as Catholicism has. Original Buddhism referred to continual conscious compassion, brotherhood, the dana paramita (meaning the perfection of charity), don’t step on the bug, all that, humility, mendicancy, the sweet sorrowful face of the Buddha (who was of Aryan origin by the way, I mean of Persian warrior caste, and not Oriental as pictured) … in original Buddhism no young kid coming to a monastery was warned that “Here we bury them alive.” He was simply given soft encouragement to meditate and be kind. The beginning of Zen was when Buddha, however, assembled all the monks together to announce a sermon and choose the first patriarch of the Mahayana church: instead of speaking, he simply held up a flower. Everybody was flabbergasted except Kashyapa, who smiled. Kashyapa was appointed the first patriarch. This idea appealed to the Chinese, like the sixth patriarch Hui-Neng who said, “From the beginning nothing ever was,” and wanted to tear up the records of Buddha’s sayings as kept in the sutras; sutras are “threads of discourse.” In a way, then, Zen is a gentle but goofy form of heresy, though there must be some real kindly old monks somewhere and we’ve heard about the nutty ones. I haven’t been to Japan. Your Maha Roshi Yoshi is simply a disciple of all this and not the founder of anything new at all, of course. On The Johnny Carson Show he didn’t even mention Buddha’s name. Maybe his Buddha is Mia.

INTERVIEWER

How come you’ve never written about Jesus? You’ve written about Buddha. Wasn’t Jesus a great guy too?

KEROUAC

I’ve never written about Jesus? In other words, you’re an insane phony who comes to my house … and … all I write about is Jesus. I am Everhard Mercurian, General of the Jesuit Army.

INTERVIEWER

What’s the difference between Jesus and Buddha?

KEROUAC

That’s a very good question. There is no difference.

INTERVIEWER

No difference?

KEROUAC

But there is a difference between the original Buddha of India, and the Buddha of Vietnam who just shaves his hair and puts on a yellow robe and is a communist agitating agent. The original Buddha wouldn’t even walk on young grass so that he wouldn’t destroy it. He was born in Gorakhpur, the son of the consul of the invading Persian hordes. And he was called Sage of the Warriors, and he had seventeen thousand broads dancing for him all night, holding out flowers, saying, “You want to smell it, my lord?” He says, “Git outta here you whore.” He laid a lot of them you know. But by the time he was thirty-one years old he got sick and tired … his father was protecting him from what was going on outside the town. And so he went out on a horse, against his father’s orders and he saw a woman dying—a man being burnt on a ghat. And he said, “What is all this death and decay?” The servant said,”That is the way things go on. Your father was hiding you from the way things go on.”

He says, “What? My father!! Get my horse, saddle my horse! Ride me into the forest!” They ride into the forest; he says, “Now take the saddle off the horse. Put it on your horse, hang it on … Take my horse by the rein and ride back to the castle and tell my father I’ll never see him again!” And the servant, Channa, cried, he said, “I’ll never see you again. I don’t care! Go on! Shoosh! Get away!!”

He spent seven years in the forest. Biting his teeth together. Nothing happened. Tormenting himself with starvation. He said, “I will keep my teeth bit together until I find the cause of death.” Then one day he was stumbling across the Rapti River, and he fainted in the river. And a young girl came by with a bowl of milk and said, “My lord, a bowl of milk.” [Slurppp] He said, “That gives me great energy, thank you my dear.” Then he went and sat under the Bo tree. Figuerosa. The fig tree. He said, “Now … [Demonstrates posture] I will cross my legs … and grit my teeth until I find the cause of death.” Two o’clock in the morning, one hundred thousand phantoms assailed him. He didn’t move. Three o’clock in the morning, the great blue ghosts!! Arrghhh!!! All accosted him. (You see I am really Scottish.) Four o’clock in the morning the mad maniacs of hell … came out of manhole covers … in New York City. You know Wall Street where the steam comes out? You know Wall Street, where the manhole covers … steam comes up? You take off them covers—yaaaaaahhh!!!!! Six o’clock, everything was peaceful—the birds started to trill, and he said, “Aha! The cause of death … the cause of death is birth.”

Simple? So he started walking down the road to Benares in India … with long hair, like you, see.

So, three guys. One says, “Hey, here comes Buddha there who, uh, starved with us in the forest. When he sits down here on that bucket, don’t wash his feet.” So Buddha sits down on the bucket … The guy rushes up and washes his feet. “Why dost thou wash his feet?” Buddha says, “Because I go to Benares to beat the drum of life.” “And what is that?” “That the cause of death is birth.” “What do you mean?” “I’ll show you.”

A woman comes up with a dead baby in her arms. Says, “Bring my child back to life if you are the Lord.” He says, “Sure I’ll do that anytime. Just go and find one family in Śrāvastī that ain’t had a death in the last five years. Get a mustard seed from them and bring it to me. And I’ll bring your child back to life.” She went all over town, man, two million people, Śrāvastī the town was, a bigger town than Benares by the way, and she came back and said, “I can’t find no such family. They’ve all had deaths within five years.” He said, “Then, bury your baby.”

Then, his jealous cousin, Devadatta (that’s Ginsberg you see … I am Buddha and Ginsberg is Devadatta), gets this elephant drunk … great big bull elephant drunk on whiskey. The elephant goes up—[Trumpets like elephant going up] with a big trunk, and Buddha comes up in the road and gets the elephant and goes like this [Kneels]. And the elephant kneels down. “You are buried in sorrow’s mud! Quiet your trunk! Stay there!” He’s an elephant trainer. Then Devadatta rolled a big boulder over a cliff. And it almost hit Buddha’s head. Just missed. Boooom! He says, “That’s Devadatta again.” Then Buddha went like this [paces back and forth] in front of his boys, you see. Behind him was his cousin that loved him … Ananda … which means “love” in Sanskrit [keeps pacing]. This is what you do in jail to keep in shape.

I know a lot of stories about Buddha, but I don’t know exactly what he said every time. But I know what he said about the guy who spit at him. He said, “Since I can’t use your abuse you may have it back.” He was great.

[Kerouac plays piano. Drinks are served.]

INTERVIEWER

There’s something there.

INTERVIEWER

My mother used to play that. I’m not sure how we can transcribe those notes onto a page. We may have to include a record of you playing the piano. Will you play that piece again for the record, Mr. Paderewski? Can you play “Alouette”?

KEROUAC

No. Only Afro-Germanic music. After all, I’m a square head. I wonder what whiskey will do to those obies.

INTERVIEWER

What about ritual and superstition? Do you have any about yourself when you get down to work?

KEROUAC

I had a ritual once of lighting a candle and writing by its light and blowing it out when I was done for the night … also kneeling and praying before starting (I got that from a French movie about George Frideric Handel) … but now I simply hate to write. My superstition? I’m beginning to suspect the full moon. Also I’m hung up on the number nine though I’m told a Piscean like myself should stick to number seven; but I try to do nine touchdowns a day, that is, I stand on my head in the bathroom, on a slipper, and touch the floor nine times with my toe tips, while balanced. This is incidentally more than yoga, it’s an athletic feat, I mean imagine calling me “unbalanced” after that. Frankly I do feel that my mind is going. So another “ritual” as you call it, is to pray to Jesus to preserve my sanity and my energy so I can help my family: that being my paralyzed mother, and my wife, and the ever-present kitties. Okay?

INTERVIEWER

You typed out On the Road in three weeks, The Subterraneans in three days and nights. Do you still produce at this fantastic rate? Can you say something of the genesis of a work before you sit down and begin that terrific typing—how much of it is set in your mind, for example?

KEROUAC

You think out what actually happened, you tell friends long stories about it, you mull it over in your mind, you connect it together at leisure, then when the time comes to pay the rent again you force yourself to sit at the typewriter, or at the writing notebook, and get it over with as fast as you can … and there’s no harm in that because you’ve got the whole story lined up. Now how that’s done depends on what kind of steel trap you’ve got up in that little old head. This sounds boastful but a girl once told me I had a steel-trap brain, meaning I’d catch her with a statement she’d made an hour ago even though our talk had rambled a million light-years away from that point … you know what I mean, like a lawyer’s mind, say. All of it is in my mind, naturally, except that language that is used at the time that it is used … And as for On the Road and The Subterraneans, no I can’t write that fast anymore … Writing The Subs in three nights was really a fantastic athletic feat as well as mental, you shoulda seen me after I was done …. I was pale as a sheet and had lost fifteen pounds and looked strange in the mirror. What I do now is write something like an average of eight thousand words a sitting, in the middle of the night, and another about a week later, resting and sighing in between. I really hate to write. I get no fun out of it because I can’t get up and say I’m working, close my door, have coffee brought to me, and sit there camping like a “man of letters” “doing his eight hour day of work” and thereby incidentally filling the printing world with a lot of dreary self-imposed cant and bombast, bombast being Scottish for pillow stuffing. Haven’t you heard a politician use fifteen hundred words to say something he could have said in exactly three words? So I get it out of the way so as not to bore myself either.

INTERVIEWER

Do you usually try to see everything clearly and not think of any words—just to see everything as clear as possible and then write out of the feeling? With Tristessa, for example.

KEROUAC

You sound like a writing seminar at Indiana University.

INTERVIEWER

I know but …

KEROUAC

All I did was suffer with that poor girl and then when she fell on her head and almost killed herself … remember when she fell on her head? She was all busted up and everything. She was the most gorgeous little Indian chick you ever saw. I say Indian, pure Indian. Esperanza Villanueva. Villanueva is a Spanish name from I don’t know where—Castile. But she’s Indian. So she’s a half Indian, half Spanish … beauty. Absolute beauty. She had bones, man, just bones, skin and bones. And I didn’t write in the book how I finally nailed her. You know? I did. I finally nailed her. She said, “Shhhhhhhhhh! Don’t let the landlord hear.” She said, “Remember, I’m very weak and sick.” I said, “I know, I’ve been writing a book about how you’re weak and sick.”

INTERVIEWER

How come you didn’t put that part in the book?

KEROUAC

Because Claude’s wife told me not to put it in. She said it would spoil the book.

But it was not a conquest. She was out like a light. On M. M., that’s morphine. And in fact I made a big run for her from way uptown to downtown to the slum district … and I said, “Here’s your stuff.” She said, “Shhhhhh!” She gave herself a shot and I said, “Ah … now’s the time.” And I got my little no-good piece. But … it was certainly justification of Mexico!

STELLA

Here kitty! He’s gone out again.

KEROUAC

She was nice, you would have liked her. Her real name was Esperanza. You know what that means?

INTERVIEWER

No.

KEROUAC

In Spanish, “hope.” Tristessa means in Spanish, “sadness,” but her real name was Hope. And she’s now married to the police chief of Mexico City.

STELLA

Not quite.

KEROUAC

Well, you’re not Esperanza—I’ll tell you that.

STELLA

No, I know that, dear.

KEROUAC

She was the skinniest … and shy … as a rail.

STELLA

She’s married to one of the lieutenants, you told me, not to the chief.

KEROUAC

She’s all right. One of these days I’m going to go see her again.

STELLA

Over my dead body.

INTERVIEWER

Were you really writing Tristessa while you were there in Mexico? You didn’t write it later?

KEROUAC

First part written in Mexico, second part written in … Mexico. That’s right. Nineteen fifty-five first part, ’56 second part. What’s the importance about that? I’m not Charles Olson, the great artist!

INTERVIEWER

We’re just getting the facts.

KEROUAC

Charles Olson gives you all the dates. You know. Everything about how he found the hound on the beach in Gloucester. Found somebody jacking off on the beach at … what do they call it? Vancouver Beach? Dig Dog River? … Dogtown. That’s what they call it, “Dogtown.” Well this is Shittown on the Merrimack. Lowell is called “Shittown on the Merrimack.” I’m not going to write a poem called Shittown and insult my town. But if I were six foot six I could write anything, couldn’t I?

INTERVIEWER

How do you get along now with other writers? Do you correspond with them?

KEROUAC

I correspond with John Clellon Holmes but less and less each year; I’m getting lazy. I can’t answer my fan mail because I haven’t got a secretary to take dictation, do the typing, get the stamps, envelopes, all that … and I have nothing to answer. I ain’t gonna spend the rest of my life smiling and shaking hands and sending and receiving platitudes, like a candidate for political office, because I’m a writer—I’ve got to let my mind alone, like Greta Garbo. Yet when I go out, or receive sudden guests, we all have more fun than a barrel of monkeys.

INTERVIEWER

What are the work-destroyers?

KEROUAC

Work-destroyers … work-destroyers. Time-killers? I’d say mainly the attentions which are tendered to a writer of “notoriety” (notice I don’t say “fame”) by secretly ambitious would-be writers, who come around, or write, or call, for the sake of the services that are properly the services of a bloody literary agent. When I was an unknown struggling young writer, as the saying goes, I did my own footwork, I hot-footed up and down Madison Avenue for years, publisher to publisher, agent to agent, and never once in my life wrote a letter to a published famous author asking for advice, or help, or, in Heaven above, had the nerve to actually mail my manuscripts to some poor author who then has to hustle to mail it back before he’s accused of stealing my ideas. My advice to young writers is to get themselves an agent on their own, maybe through their college professors (as I got my first publishers through my prof Mark Van Doren), and do their own footwork, or “thing” as the slang goes … So the work-destroyers are nothing but certain people.

The work-preservers are the solitudes of night, “when the whole wide world is fast asleep.”

INTERVIEWER

What do you find the best time and place for writing?

KEROUAC

The desk in the room, near the bed, with a good light, midnight till dawn, a drink when you get tired, preferably at home, but if you have no home, make a home out of your hotel room or motel room or pad: peace. [Picks up harmonica and plays.] Boy, can I play!

INTERVIEWER

What about writing under the influence of drugs?

KEROUAC

Poem 230 from Mexico City Blues is a poem written purely on morphine. Every line in this poem was written within an hour of one another … high on a big dose of M. [Finds volume and reads.]

Love’s multitudinous boneyard of decay,

An hour later:

The spilled milk of heroes,

An hour later:

Destruction of silk kerchiefs by dust storm,

An hour later:

Caress of heroes blindfolded to posts,

An hour later:

Murder victims admitted to this life,

An hour later:

Skeletons bartering fingers and joints,

An hour later:

The quivering meat of the elephants of kindness

being torn apart by vultures,

(See where Ginsberg stole that from me?) An hour later:

Conceptions of delicate kneecaps.

Say that, Saroyan.

SAROYAN

Conceptions of delicate kneecaps.

KEROUAC

Very good. Fear of rats dripping with bacteria. An hour later: Golgotha Cold Hope for Gold Hope. Say that.

SAROYAN

Golgotha Cold Hope for Cold Hope.

KEROUAC

That’s pretty cold.

An hour later:

Damp leaves of autumn against the

wood of boats,

An hour later:

Seahorse’s delicate imagery of glue.

Ever see a little seahorse in the ocean? They’re built of glue … Did you ever sniff a sea horse? No, say that.

SAROYAN

Seahorse’s delicate imagery of glue.

KEROUAC

You’ll do, INTERVIEWER.

Death by long exposure to defilement.

SAROYAN

Death by long exposure to defilement.

KEROUAC

Frightening ravishing mysterious beings concealing their sex.

SAROYAN

Frightening ravishing mysterious beings concealing their sex.

KEROUAC

Pieces of the Buddha-material frozen and sliced

microscopically

In Morgues of the North.

SAROYAN

Hey, I can’t say that. Pieces of the Buddha-material frozen and sliced microscopically in Morgues of the North.

KEROUAC

Penis apples going to seed.

SAROYAN

Penis apples going to seed.

KEROUAC

The severed gullets more numerous than sands.

SAROYAN

The severed gullets more numerous than sands.

KEROUAC

Like kissing my kitten in the belly.

SAROYAN

Like kissing my kitten in the belly.

KEROUAC

The softness of our reward.

SAROYAN

The softness of our reward.

KEROUAC

Is he really William INTERVIEWER’s son? That’s wonderful! Would you mind repeating that?

INTERVIEWER

We should be asking you a lot of very straight serious questions. When did you meet Allen Ginsberg?

KEROUAC

First I met Claude.* And then I met Allen and then I met Burroughs. Claude came in through the fire escape … There were gunshots down in the alley—Pow! Pow!—and it was raining, and my wife says, “Here comes Claude.” And here comes this blond guy through the fire escape, all wet. I said, “What’s this all about, what the hell is this?” He says, “They’re chasing me.” Next day in walks Allen Ginsberg carrying books. Sixteen years old with his ears sticking out. He says, “Well, discretion is the better part of valor!” I said, “Aw shutup. You little twitch.” Then the next day here comes Burroughs wearing a seersucker suit, followed by the other guy.

INTERVIEWER

What other guy?

KEROUAC

It was the guy who wound up in the river. This was the guy from New Orleans that Claude killed and threw in the river. Stabbed him twelve times in the heart with a Boy Scout knife.

When Claude was fourteen he was the most beautiful blond boy in New Orleans. And he joined the Boy Scout troop … and the Boy Scout master was a big redheaded fairy who went to school at Saint Louis University, I think it was.

And he had already been in love with a guy who looked just like Claude in Paris. And this guy chased Claude all over the country; this guy had him thrown out of Baldwin, Tulane, and Andover Prep … It’s a queer tale, but Claude isn’t a queer.

INTERVIEWER

What about the influence of Ginsberg and Burroughs? Did you ever have any sense then of the mark the three of you would have on American writing?

KEROUAC

I was determined to be a “great writer,” in quotes, like Thomas Wolfe, see … Allen was always reading and writing poetry … Burroughs read a lot and walked around looking at things. The influence we exerted on one another has been written about over and over again … We were just three interested characters, in the interesting big city of New York, around campuses, libraries, cafeterias. You can find a lot of the details in Vanity … in On the Road, where Burroughs is Bull Lee and Ginsberg is Carlo Marx, and in Subterraneans, where they’re Frank Carmody and Adam Moorad, respectively. In other words, though I don’t want to be rude to you for this honor, I am so busy interviewing myself in my novels, and have been so busy writing down these self-interviews, that I don’t see why I should draw breath in pain every year for the last ten years to repeat and repeat to everybody who interviews me (hundreds of journalists, thousands of students) what I’ve already explained in the books themselves. It begs sense. And it’s not that important. It’s our work that counts, if anything at all, and I’m not too proud of mine or theirs or anybody’s since Thoreau and others like that, maybe because it’s still too close to home for comfort. Notoriety and public confession in the literary form is a frazzler of the heart you were born with, believe me.

INTERVIEWER

Allen once said that he learned how to read Shakespeare, that he never did understand Shakespeare until he heard you read Shakespeare to him.

KEROUAC

Because in a previous lifetime, that’s who I was.

How like a winter hath my absence been from thee?

The pleasure of the fleeting year … what freezings

have I felt? What dark days seen? Yet Summer with his

lord surcease hath laid a big turd in my orchard.

And one hog after another comes to eat

and break my broken mountain trap, and my mousetrap

too! And here to end the sonnet, you must make sure

to say, tara-tara-tara!!!!!!

INTERVIEWER

Is that spontaneous composition?

KEROUAC

Well, the first part was Shakespeare … and the second part was …

INTERVIEWER

Have you ever written any sonnets?

KEROUAC

I’ll give you a spontaneous sonnet. It has to be what, now?

INTERVIEWER

Fourteen lines.

KEROUAC

That’s twelve lines with two dragging lines. That’s where you bring out your heavy artillery.

Here the fish of Scotland seen your eye

and all my nets did creak …

Does it have to rhyme?

INTERVIEWER

No.

KEROUAC

My poor chapped hands fall awry

and seen the Pope, his devilled eye.

And maniacs with wild hair hanging about my room

and listening to my tomb

which does not rhyme.

Seven lines?

INTERVIEWER

That was eight lines.

KEROUAC

And all the orgones of the earth will crawl

like dogs across the graves of Peru

and Scotland too.

That’s ten.

Yet do not worry, sweet angel of mine

That hast thine inheritance

imbedded in mine.

INTERVIEWER

That’s pretty good, Jack. How did you do that?

KEROUAC

Without studying dactyls … like Ginsberg … I met Ginsberg … I’d hitchhiked all the way back from Mexico City to Berkeley, and that’s a long way baby, a long way. Mexico City across Durango … Chihuahua … Texas. I go back to Ginsberg, I go to his cottage, I say, “Hah, we’re gonna play the music.” He says, “You know what I’m going to do tomorrow? I’m going to throw on Mark Schorer’s desk a new theory of prosody! About the dactylic arrangements of Ovid!” [laughter.]

I said, “Quit, man. Sit under a tree and forget it and drink wine with me … and Phil Whalen and Gary Snyder and all the bums of San Francisco. Don’t you try to be a big Berkeley teacher. Just be a poet under the trees … and we’ll wrestle and we’ll break holds.” And he did take my advice. He remembered that. He said, “What are you going to teach … you have parched lips!” I said, “Naturally, I just came from Chihuahua. It’s very hot down there, phew! You go out and little pigs rub against your legs. Phew!”

So here comes Snyder with a bottle of wine … and here comes Whalen, and here comes what’s his name, Rexroth, and everybody … and we had the poetry renaissance of San Francisco.

INTERVIEWER

What about Allen getting kicked out of Columbia? Didn’t you have something to do with that?

KEROUAC

Oh, no … he let me sleep in his room. He was not kicked out of Columbia for that. The first time he let me sleep in his room, and the guy that slept in our room with us was Lancaster who was descended from the White Roses or Red Roses of England. But a guy came in … the guy that ran the floor and he thought that I was trying to make Allen, and Allen had already written in the paper that I wasn’t sleeping there because I was trying to make him, but he was trying to make me. But we were just actually sleeping. Then after that he got a pad … he got some stolen goods in there … and he got some thieves up there, Vicky and Huncke. And they were all busted for stolen goods, and a car turned over, and Allen’s glasses broke, it’s all in John Holmes’s Go.

Allen Ginsberg asked me when he was nineteen years old, “Should I change my name to Allen Renard?” “You change your name to Allen Renard I’ll kick you right in the balls! Stick to Ginsberg …” and he did. That’s one thing I like about Allen. Allen Renard!!!

INTERVIEWER

What was it that brought all of you together in the fifties? What was it that seemed to unify the Beat generation?

KEROUAC

Oh the Beat generation was just a phrase I used in the 1951 written manuscript of On the Road to describe guys like Moriarty who run around the country in cars looking for odd jobs, girlfriends, kicks. It was thereafter picked up by West Coast Leftist groups and turned into a meaning like “Beat mutiny” and “Beat insurrection” and all that nonsense; they just wanted some youth movement to grab on to for their own political and social purposes. I had nothing to do with any of that. I was a football player, a scholarship college student, a merchant seaman, a railroad brakeman on road freights, a script synopsizer, a secretary … And Moriarty-Cassady was an actual cowboy on Dave Uhl’s ranch in New Raymer, Colorado … What kind of beatnik is that?

INTERVIEWER

Was there any sense of “community” among the Beat crowd?

KEROUAC

That community feeling was largely inspired by the same characters I mentioned, like Ferlinghetti, Ginsberg; they are very socialistically minded and want everybody to live in some kind of frenetic kibbutz, solidarity and all that. I was a loner. Snyder is not like Whalen, Whalen is not like McClure, I am not like McClure, McClure is not like Ferlinghetti, Ginsberg is not like Ferlinghetti, but we all had fun over wine anyway. We knew thousands of poets and painters and jazz musicians. There’s no “Beat crowd” like you say … What about Scott Fitzgerald and his “lost crowd,” does that sound right? Or Goethe and his “Wilhelm Meister crowd”? The subject is such a bore. Pass me that glass.

INTERVIEWER

Well, why did they split in the early sixties?

KEROUAC

Ginsberg got interested in left wing politics … Like Joyce, I say, as Joyce said to Ezra Pound in the 1920s, “Don’t bother me with politics, the only thing that interests me is style.” Besides I’m bored with the new avant-garde and the skyrocketing sensationalism. I’m reading Blaise Pascal and taking notes on religion. I like to hang around now with nonintellectuals, as you might call them, and not have my mind proselytized, ad infinitum. They’ve even started crucifying chickens in happenings, what’s the next step? An actual crucifixion of a man … The Beat group dispersed as you say in the early sixties, all went their own way, and this is my way: home life, as in the beginning, with a little toot once in a while in local bars.

INTERVIEWER

What do you think of what they’re up to now? Allen’s radical political involvement? Burroughs’s cut-up methods?

KEROUAC

I’m pro-American and the radical political involvements seem to tend elsewhere … The country gave my Canadian family a good break, more or less, and we see no reason to demean said country. As for Burroughs’s cut-up method, I wish he’d get back to those awfully funny stories of his he used to write and those marvelously dry vignettes in Naked Lunch. Cut-up is nothing new, in fact that steel-trap brain of mine does a lot of cutting up as it goes along … as does everyone’s brain while talking or thinking or writing … It’s just an old Dada trick, and a kind of literary collage. He comes out with some great effects though. I like him to be elegant and logical and that’s why I don’t like the cut-up which is supposed to teach us that the mind is cracked. Sure the mind’s cracked, as anybody can see in a hallucinated high, but how about an explanation of the crackedness that can be understood in a workaday moment?

INTERVIEWER

What do you think about the hippies and the LSD scene?

KEROUAC

They’re already changing, I shouldn’t be able to make a judgment. And they’re not all of the same mind. The Diggers are different … I don’t know one hippie anyhow … I think they think I’m a truck-driver. And I am. As for LSD, it’s bad for people with incidence of heart disease in the family [knocks microphone off footstool … recovers it].

Is there any reason why you can see anything good in this here mortality?

INTERVIEWER

Excuse me, would you mind repeating that?

KEROUAC

You said you had a little white beard in your belly. Why is there a little white beard in your mortality belly?

INTERVIEWER

Let me think about it. Actually it’s a little white pill.

KEROUAC

A little white pill?

INTERVIEWER

It’s good.

KEROUAC

Give me.

INTERVIEWER

We should wait till the scene cools a little.

KEROUAC

Right. This little white pill is a little white beard in your mortality which advises you and advertises to you that you will be growing long fingernails in the graves of Peru.

INTERVIEWER

Do you feel middle-aged?

KEROUAC

No. Listen, we’re coming to the end of the tape. I want to add something on. Ask me what Kerouac means.

INTERVIEWER

Jack, tell me again what Kerouac means.

KEROUAC

Now, kairn. K (or C) A-I-R-N. What is a cairn? It’s a heap of stones. Now Cornwall, cairn-wall. Now, right, kern, also K-E-R-N, means the same thing as cairn. Kern. Cairn. Ouac means “language of.” So, Kernouac means the language of Cornwall. Kerr, which is like Deborah Kerr. Ouack means language of water. Because Kerr, Carr, etc., means water. And cairn means heap of stones. There is no language in a heap of stones. Kerouac. Ker-(water), ouac-(language of). And it’s related to the old Irish name, Kerwick, which is a corruption. And it’s a Cornish name, which in itself means cairnish. And according to Sherlock Holmes, it’s all Persian. Of course you know he’s not Persian. Don’t you remember in Sherlock Holmes when he went down with Dr. Watson and solved the case down in old Cornwall and he solved the case and then he said, “Watson, the needle! Watson, the needle …” He said, “I’ve solved this case here in Cornwall. Now I have the liberty to sit around here and decide and read books, which will prove to me … why the Cornish people, otherwise known as the Kernuaks, or Kerouacs, are of Persian origin. The enterprise which I am about to embark upon,” he then said, after he got his shot, “is fraught with eminent peril, and not fit for a lady of your tender years.” Remember that?

MCNAUGHTON

I remember that.

KEROUAC

McNaughton remembers that. McNaughton. You think I would forget the name of a Scotsman?

* “Claude,” Kerouac’s pseudonym for Lucien Carr, is also used in Vanity of Duluoz.